The Mindset Shift needed to Improve Product Teams

We learn a me-centric mindset early on but this inhibits strong collaboration. Tyler shares practical examples of how to shift to an others-first mindset to build better products.

The most critical attribute of an effective design process is not better software, it's not Scrum or Agile, and it's not a new kind of design system. Those are all great facets. But it's far more foundational than any tool or technique we could adopt. It's humility.

The fact is, we've been hardwired with a me-centered mindset from our youth. This is deeply ingrained in each of us. As a kid, I was at the center of the universe, right? I was the main character of the story. And when it came to the thoughts and the plans I had for my future, like many of you, I was consistently asked the questions "what do you want to be when you grow up?", "what are you going to accomplish?", "what kind of future will make you most happy?". All aspects of life had me constantly preparing for the kind of career that would ultimately define and fulfill me. And that was equally true in college. I went to school for graphic design where every project I worked on had me functioning as the only team member and the client. It was always my vision from the beginning to the end. And so we work our whole young lives towards a career with this emphasis on me.

The impact of being Me-Centered

All of a sudden, we get hired to work alongside others, being informed by others, creating things for others, asking questions of others. And it's truly incredibly jarring. So when I design out of a me-centered mindset, the truth is, I'm only designing for me. And I've said this a lot in the past, but what I do as a visual designer, I'm painting pictures for the great gallery of my own design achievements. I could care less about how positive of an impact it may have on the lives of others or how I might lift up the talents of my team. I'm only concerned with what others think about me. And I'll tell you, my heart just aches when I consider all of the effort I poured into elevating and guarding my reputation as a professional designer over these past 15 years.

When we work out of a me-centered mindset, we completely cut the most critical voices out of the equation. We insist on doing what we do in a vacuum without inviting input and critique and collaboration which will inevitably sabotage the entire process. Me-centered design elevates the priority of your own contribution as it minimises the work of everyone else.

We believe that our expertise is sufficient when the customers are the real experts. They're the ones who can offer the most valuable input from the very beginning. They're the ones who will use your product long after you finish building it. And when we design without considering their needs, their experiences and the overall impact our work may have on their lives, we're going to miss the mark every single time. We'll come out of every project with great wireframes or great mock ups, but just a lousy product.

Overcoming Me-Centeredness

This topic grew out of an effort to define our own design process at Pixo. We wanted to answer the question of how can we do our best work more consistently? What makes our process most impactful? And the deeper we dug into these questions, the more we uncovered this common thread that all of our best work that we had done on all of our projects, all of it has been directly connected to the amount of humility that we employed on the project.

So if we're going to effectively introduce humility into our own process, we have to first acknowledge that me-centered thinking and how it pervades our own lives currently. We need to reckon with the influence of the me-centered world around us.

Think about the following four questions:

- When you're working on a task do you invite people in to regularly critique your work or do you wait until everything is just right before you share it with others?

- When researching a future project, do you speak with potential users to understand their needs or do you rely on your own experience and your own understanding for direction?

- Do you consider your client or the stakeholders to be an ally, someone to partner with or someone who will most likely get in the way?

- When you receive critical feedback, do you take it as an opportunity to improve yourself and your work or do you throw a fit and determine all of the reasons why they are wrong?

All right, How do you do? I'm confident we're not hitting the home runs here. I know I'm not.

To illustrate the changes that are needed we're going to walk through Pixo's own design process. And with each phase, I'll share some thoughts and some practices we typically utilize to help us keep others at the center of our work.

Our process consists of four D's. Discover, Define, Design, Develop. Pretty simple. I'm sure you've got something like this as well.

Discover

As the designer, specifically as the visual designer, it is my immediate temptation to disengage from the discovery phase. I'm just here to kick out mockups, right? That's a me-centered mentality. Rather, we as designers must walk alongside our content strategists, our UX designers, our researchers as they do the hard work of research. We need to ask to participate in their interviews with audience members, be an observer at each activity and listen intently to the conversations they're having.

Another issues is that I'm quick to assume that my eye for design is far better than the client's. I can whip up something from my own imagination without their input and it'll be right on target. Don't even worry about it. But that's absolutely untrue. I am just now entering this project where they've had a vision for this product for months, if not years. It's my job to help materialize what they already visualize. So we must conduct activities that help the client communicate their vision in a visual way.

Humility in discovery

One activity that we like to use is we call it the gut test. So in this activity, we invite a diverse group of people from the organization to review 15 to 20 different examples of designs from around the web. And with each example, we ask our participants to answer the question, how accurately does this design represent your vision for the new website?

We'll send out an online survey with the images to gather their thoughts. And then we'll have this follow-up discussion with the entire group to review the results. And this is always such an eye-opening activity. I love it. It empowers the client to actually pair pictures with their thoughts.

"When I say that I want our website to be modern or bold or approachable, this is what I mean right here."

So instead of assuming that I know what they mean, they can articulate their vision more precisely.

Define

Define is less of a phase and it's more of a pivot point. When we define, our goal as designers is to synthesize and communicate all we've learned from our research. And then we want to set an initial course for the design itself.

It'd be easy to conduct our research and simply say,"OK, thanks, we'll take it from here". But how do we know that we're walking away with the right information? So we make the time to share with the client all that we've learned with the discovery findings meeting. When we share our findings with the client, we ensure that our research is accurate and it's complete. And this is a chance for the experts to call out any inconsistencies or blind spots in our understanding.

Then the other facet of the phase is setting the course for design in collaboration with the client. It is a great temptation as designers to run off with just the first good idea we have and make it a reality. But if we head off in some direction that seems right to us alone, even if it's off by just a few degrees, we'll end up miles away from the client's vision.

Humility in Define

We solve this problem at Pixo by using something we call design palettes. A design palette is just a collage of styles like colours and typography and buttons which serve eventually as the visual DNA for the entire product. This is very much derived from Samantha Warren's concept of style tiles. This is a fantastic tool for collaboration as well.

As a designer, I develop three to five of these palettes. Then I work with the client to review each palette and determine which collection is nearing the mark. So together we grab the colours from this palette or the type from this palette and the buttons from this other palette to form a set of styles that the client and I feel best represent their organization and their vision for the product. Once we have our final palette, I can grab my paintbrush and I can begin designing mockups with confidence, knowing that the perspectives and the desires of others have been accommodated.

Design

When I would design, I was like a train just headed into a long tunnel for about two weeks. And then I'd emerge on the other side with a handful of nearly finished mockups. But here's the thing, I preferred the tunnel because I didn't want anyone to see my work until it was finished. It wasn't good enough. It wasn't up to my standard of quality. I was afraid to share it. What would others think of me and think of me as a designer? I was guarding my reputation instead of inviting others to help me refine it. I was more concerned about me and less about them.

And let me tell you, designer, let people in. Your work is unfinished. It's ugly because it's going to be until it's done. No one looks at a big hole in the ground at a construction site and says, oh, man, that engineer has no idea what they're doing. In fact, the wise engineer says, hey, can you take a look at this hole and make sure it's right? People are going to depend on the building that goes here. And I don't want it to collapse.

Humility in Design

We have to kill our pride. Now, how can we do that practically? We do that by holding frequent critiques with fellow designers. Don't wait until it's all finished. The moment you have a rough concept, share it with your team. Invite them to review it with a critical eye. Share your progress with the client even when it's half baked or even if it's quarter baked. If you're feeling unsure about a decision you've made, look to them for their affirmation. I guarantee you the right clients will appreciate it. They'll be more invested because of it.

And then share the design with your engineers, too, as early as possible. Do not wait until it's 100 percent complete and ready for development. Your design is not 100 percent complete until it's developed. You can't design a website in Figma and call it a website because it's not on the web.

Develop

It's our tendency as designers to do what Dan Mall refers to as the dead drop. We package up our design files, we hook them over the wall to our engineers, and we just hope for the best. Right. Maybe you've done that before.

Humility in Develop

We need to schedule regular collaboration sessions where you and your engineers are combing through the working product together. Get familiar with the code yourself and speak in their language. Don't abandon them - be in it with them.

And finally, now that we have a partially working product, we have to invite future users to test it. Go back to those audience members you first interviewed and see what they think. Conduct your user test. See what's working and what's not working from their perspective. Let them critique it and refine it. Remember, it's ultimately for them.

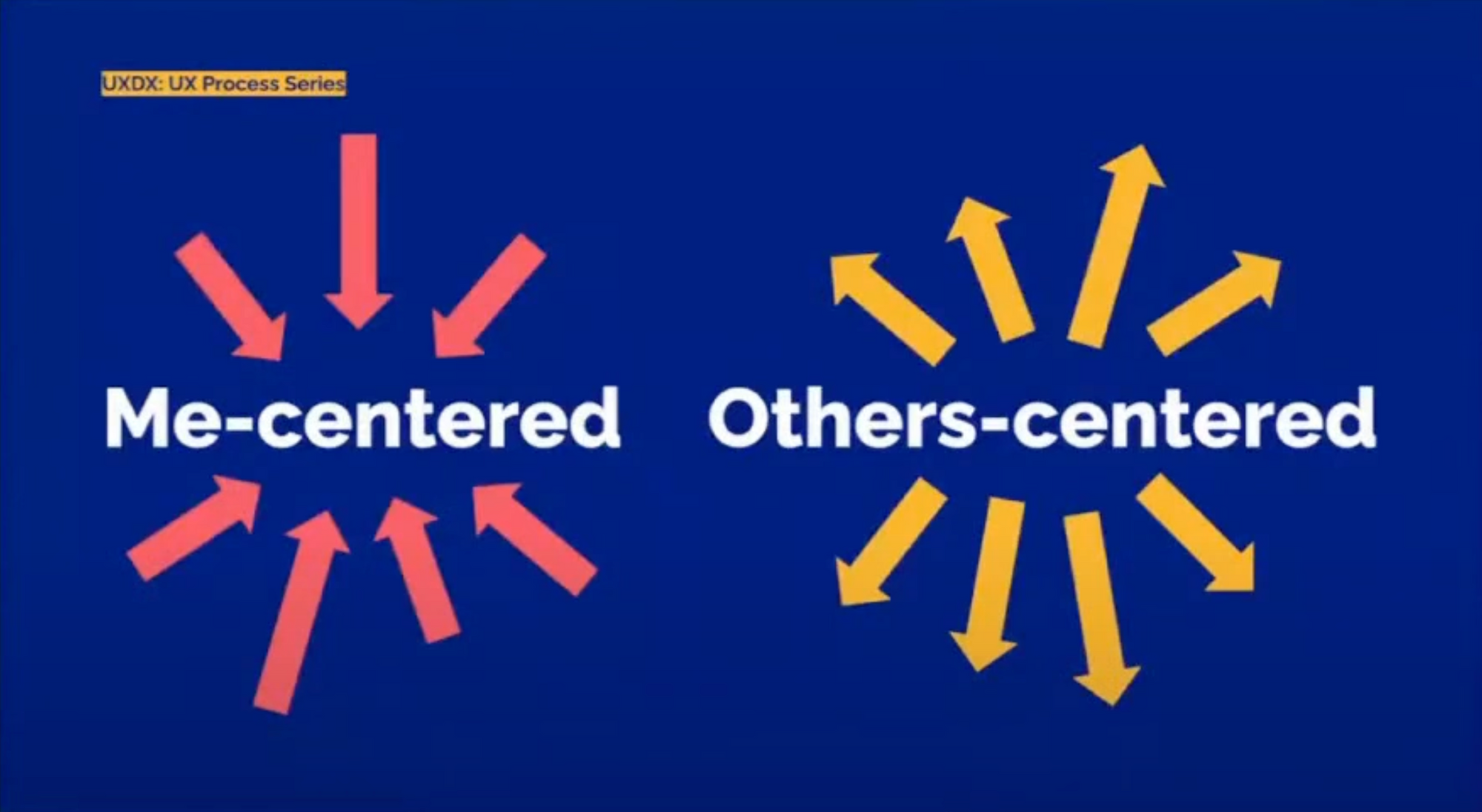

Pushbacks

When we hear that word humility, I think many of us equate it with having maybe a low view of yourself, right? Like it may be considered humble to think little of your strengths or your position or even your value as a team member. But it's not quite right. True humility is not a diminishing of your capabilities, it's actually a recognition of your inabilities. You do have many strengths. You are a worthy and equal member of your team. And at the same time, you are not the end all be all source of success. You're only a piece of the puzzle. If we're going to work in humility as professionals, as UX designers, visual designers, as whomever, then we must see how dependent we truly are on the people around us. That's the heart of humility. It is an all encompassing focal shift from ourselves to the people around us from being me-centered to other-centered.

Another challenges is that it requires a great deal of hard work, too. This isn't a new tool or a technique to implement. This is a work of personal transformation. This is a rewiring and unlearning. But I promise you, it is worth it. I'm not saying this from the summit - I am not the divine humble designer here. I'm at the base here hoping to change along with you.

Do you wish to rise? Begin by descending. You plant a tower that will pierce the clouds, lay first the foundation of humility. - St. Augustine of Hippo

Outcomes

When we had shifted our mindset from being me-centered to others-centered, our work radically improved. When we built our design process on a foundation of humility, when we elevated the needs and the perspectives and the gifts of others above our own, we produced the kind of work that truly makes us proud.