The Organisational Changes required to support Cross-Functional Product Teams

The functional structure is dominant in most organisations. But like most things in life one-size doesn't fit all. How can companies shift to support cross-functional product development?

In the last post I talked about the evolution of software delivery from Waterfall all the way through to Product Teams. This evolution requires wholesale changes in a number of areas outside of the delivery teams themselves. In this post I'm going to talk through the one of those areas of change: the structural and management changes.

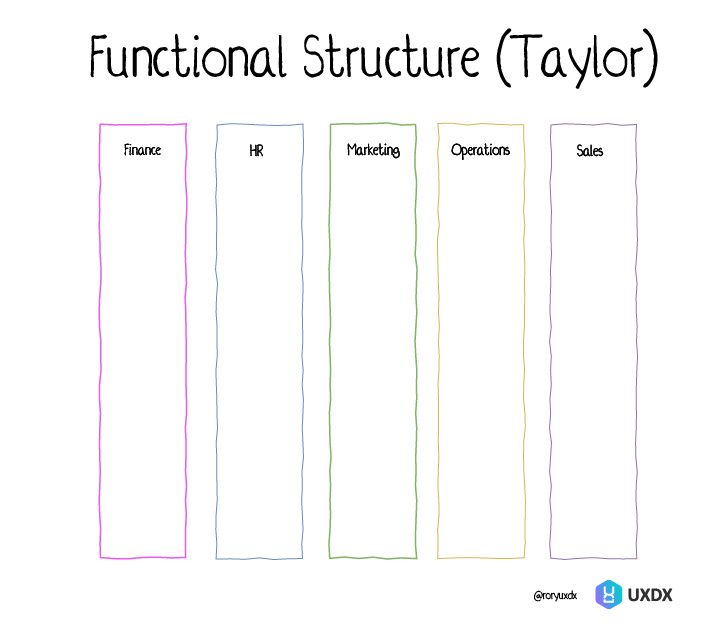

But first, we have to start with some history again. Back in the late 19th century there was a movement to apply some structure and rigour to organisational design. One of the most influential people during this time was Frederick Taylor, author of the book The Principles of Scientific Management. Recognising that a single person cannot do, or manage, every task in a large company Taylor proposed that the work of the organization should be divided into various functions. This functional approach led to increased specialisation in the respective areas which, in turn, led to increased productivity. The success of specialisation is why most companies today follow a functional structure with recognisable departments such as purchasing, sales, finance, marketing, legal, operations etc.

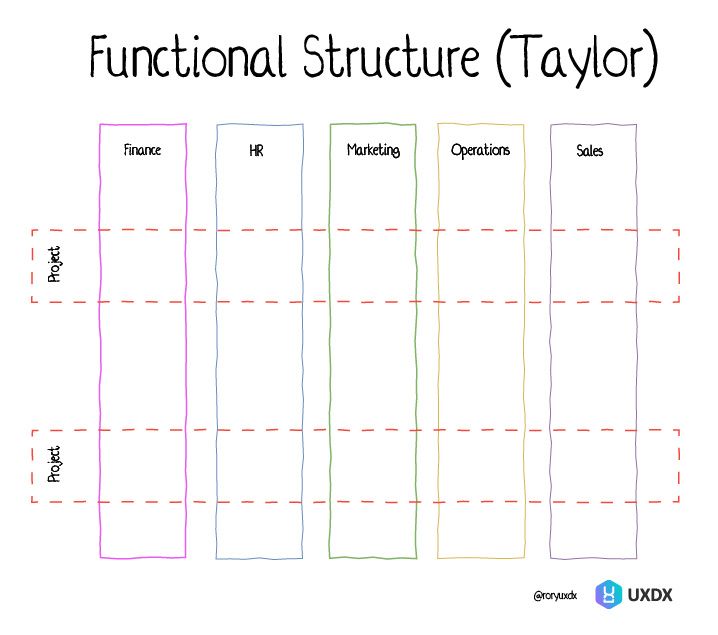

The functional structure assumes that the state of the company is pretty static. Back in the late 19th century large changes, such as the introduction of a new product or compliance with new regulation, were rare. These types of changes cannot be handled separately by each function as they require coordinated effort across multiple functions. Projects were created in order to manage these large cross-functional changes. Projects are less efficient for each of the teams involved but, since the core assumption of a functional structure is that large changes are rare, the efficiency of the function outweighs the inefficiency of the project.

As businesses grew and became more complex specialisation grew so each top-level function, or department, created sub-levels of functional separation. For example Marketing might include Brand, PR, Digital, SEO, and Social among others. When IT emerged as a new discipline it was typically placed as a sub-function into the Finance department – Finance was chosen to make sure that there was tight control on the costs of this new, and expensive, function.

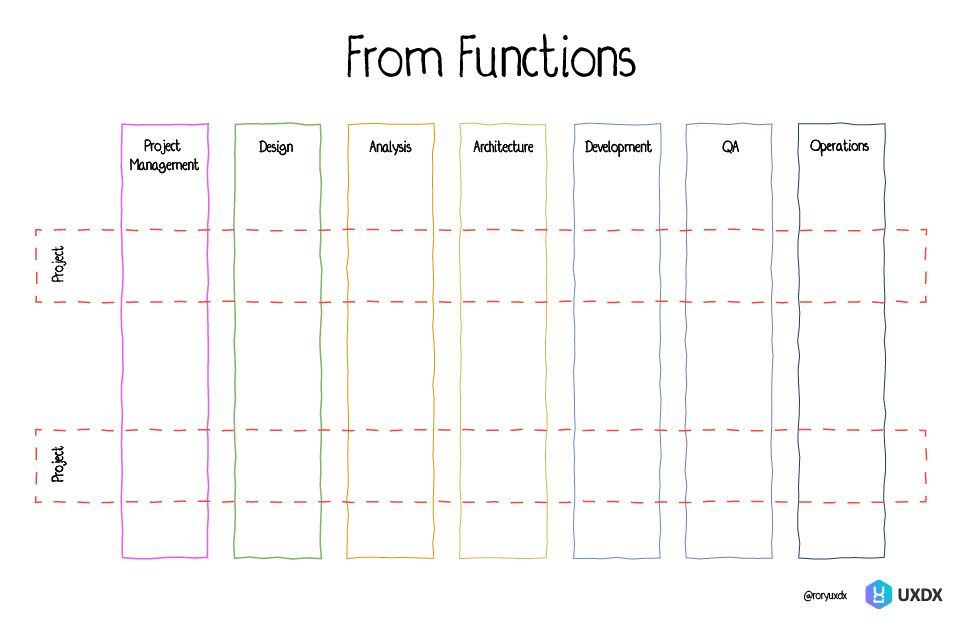

Over time, as product development became more complex, further specialisation emerged within the parent IT function such as Project Management, Business Analysis, Architecture, Frontend Development, Backend Development, QA, Operations and more. These specialisations emerged slowly, and the functional structure was so ingrained in organisations that people didn’t question the approach. But these IT functions are quite different to other organisational functions.

The conscious decision when setting up a functional structure is that the company is prioritising the efficiency of the function over the efficiency of a project.

The underlying assumption in a functional structure is that each function can do its job largely independently of other functions. While there definitely needs to be sharing of information Marketing can market, Sales can sell, Finance can track the accounts and HR can hire and manage people. The IT functions can’t provide value outside of a project - cross functional collaboration is a norm not an exception.

In software development there is a concept of technical debt, which can be summarised as the extra work that arises when code that is easy to implement in the short run is used instead of applying the best overall solution. The same is true for organisations. While they may seem static, organisations are constantly evolving – people get promoted into new roles, new specialisations come into being (SEO, Social), or people move on and aren’t replaced. In the same way with technical debt, unless you consciously plan your organisational structure and pay down the debt it will lead to poorer performance over time.

Software has moved from being an edge case to being critical for nearly every department within a company which has led to ever increasing demands for software projects and releases. Companies have tried to scale project delivery but there is a limit to how well they can scale largely constrained by the fact that the functional structure is not optimised for projects. One of the major warning signs for me is the number of people required to support the scaling projects – people responsible for governance and tracking of projects, resource managers, environment managers, release managers and an increasing number of portfolio and programme managers.

What alternatives do we have for the functional structure?

Andy Grove, author of High Output Management, highlights a second common organisational structure – cross functional, mission-oriented teams. The key benefit of cross-functional teams is awareness of customer needs and the ability to react accordingly. In fact, Grove goes as far as to say:

“The only advantage of the mission-oriented form is that Individual units can stay in touch with the needs of their business or product areas and initiate changes rapidly when those needs change. That is it. All other considerations favour the functional-type of organisation.”

But even with that damning statement, while Grove was CEO of Intel, 33% of his teams were cross-functional because responding to the needs of customers is critical for businesses to survive.

The ROI for software delivery tends to be impressive. The benefits significantly outweigh the costs which is why projects can get away with asking for increased budgets so often. This means that speed to deliver is often more critical than total cost – the cost will be recovered quickly so the sooner it is in the market the sooner it will be returning value.

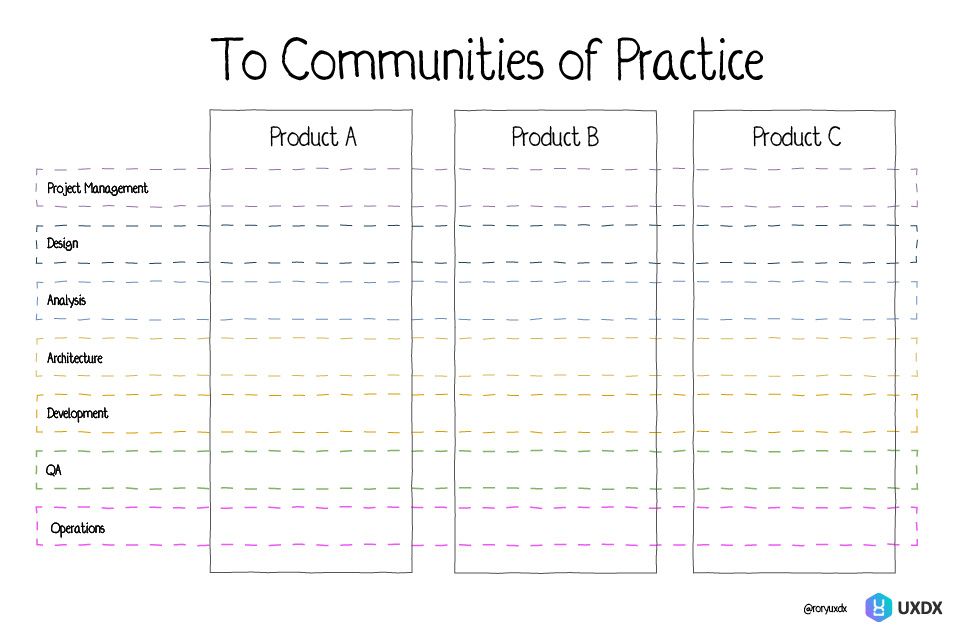

Therefore, in software development the efficiency of the total delivery is more important than the cost efficiency of individual functions. Cross-functional, mission oriented teams are the best structure for software delivery.

WIIFM (What’s in it for me)?

There are a number of different people involved in the shift to cross-functional teams, but the people most impacted are the functional managers. And we need to get their buy-in for the change to be successful which means that we need to highlight the value for them personally.

A functional manager has a lot of responsibilities including recruitment, line management, performance management, resource allocation, functional strategy, budget management and operational support. A cross-functional structure changes a number of these areas of responsibility.

With a cross-functional product structure people are assigned long-term to a product instead of jumping quickly between projects. This means that the resource allocation and budget management tasks shift from the function to the product. As people are assigned long term to the product team it also makes sense to distribute line management and performance management tasks between the product and function as well.

By removing a lot of the administrative tasks, the functional manager can shift to be more focused on the functional strategy - leading communities of practice to identify the areas for improvement within their practice and supporting their people on the journey of change. To reduce the leaning anxiety of taking on this new responsibility the functional managers should be supported through personal coaching as well as training budgets for them and their teams.

I’ve never heard any functional manager say they enjoy the administrative side of their roles so you would think the reduction in this part of the role would be seen as a positive step. Unfortunately, this simplistic view of the world misses out on the emotional side of change. There are power structures in all organisations and these are often linked to the size of your budget or the number of people in your team. By shifting the functional manager from a position of authority (line management and resource allocation) to a position of influence (strategic direction) you challenge the perception of power of the line managers. To combat this perception you need to elevate, publicly, the importance of the strategic role of functional management both through regular communications both written and company presentations.

Approaching Change

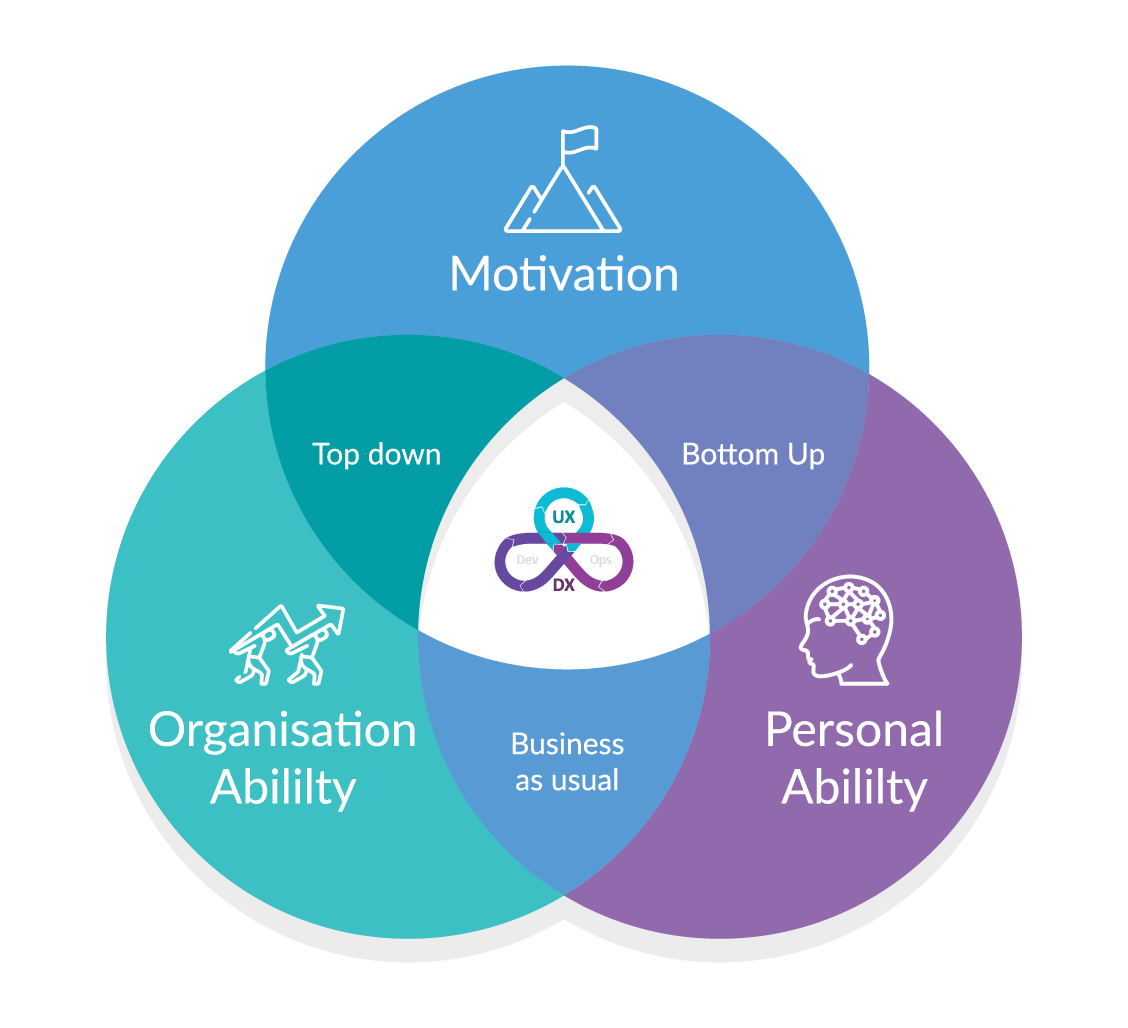

Let’s assume that you are convinced on the need to move from functional structure and the functional managers are equally motivated. That is a huge achievement but unfortunately we’re still only on step 1 of the journey because change needs more than motivation. The three key ingredients are: Motivation, Personal Ability and Organisational Ability.

Functional managers have been successful with the current way of working, having risen through the ranks to lead their respective functions. They have mastered the current way of working, they know how to manage their teams and they are clear on how to manage up as well. When things are working well "change" only represents the potential for loss.

- What will my role shift to?

- Will I be any good at it?

- What will happen if I’m not?

- What will happen if this new structure is more efficient?

- Will that reflect badly on how I was managing before?

These types of questions represent learning anxiety and survival anxiety, which everyone faces when presented with a new challenge. The key to delivering the Personal Ability to change is to ensure that learning anxiety is less than survival anxiety, which can be achieved either by increasing survival anxiety or decreasing learning anxiety.

Increasing survival anxiety

Some companies are in crisis. Things are going very wrong and if something doesn’t change soon then the company may go bust. Other times senior executives create a crisis even when none exists in order to spur on the necessary change within the organisation. A final approach could be directed at a particular manager, making it clear that their performance is sub-par and unless improvements are made then their job may not be tenable. The problem with all of these approaches is that they are very stressful on the individuals impacted. While it may be enough to get the change through you will have harmed the trust that the people have in the organisation, which can have future impacts on productivity and commitment.

Decreasing Learning Anxiety

Google ran a multi-year analysis of team performance to identify the key ingredients of high performing teams. Psychological safety came out as the number one indicator of strong performance. Psychological safety means that the team members are comfortable trying new things to improve how they work as well as being comfortable admitting their mistakes because they know that this will not be used against them. A great example of psychological safety in practice is the consultancy, K2K Emocionando, who specialise in transforming companies along cross functional lines. One of their 10 non-negotiable starting points on any transformation is that nobody will be let go. Everyone will get the necessary training and support to move into a role that provides real value for the organisation.

Organisational Ability

The last major ingredient for successful change is the organisational ability to change. People often refer to a shift of this magnitude in an organisation as a cultural change. And culture is hard to change because it is the embodiment of decades of consistency in a particular way of working. When exposed to a proposed large-scale change people are attuned to listening to actions rather than words because often there is little follow through after the initial announcements. This means that there needs to be clear support from the top demonstrated through the way that the functional managers are being managed and assessed. The role of the functional manager changes considerably with the shift to cross-functional teams so the KPI’s and expectations placed on these people need to change in parallel.

KPI’s that once were focused on headcount and budget (CapEx vs Opex utilisation) need to shift to focus on how the function contributes to product delivery efficiency. This will require experimentation in KPI’s and flexibility over time as the functional managers need the psychological safety to experiment and iterate their way towards better ways of working.

Conclusion

To wrap it up, the functional structure that exists in other departments doesn’t make sense in IT as the functions in IT must coordinate in order to deliver value. Coupled with the need to be reactive to customer needs and the priority of speed over cost this means that cross functional teams are more optimal. The shift to cross functional teams is hard though, particularly on the functional managers. Supporting them through coaching, training and elevating the importance of the strategic work is critical for securing their buy in. Finally, this needs to happen in parallel with a shift in the expectations and management approach from senior management or it will result in a return to the status quo.

If you want to learn more check out the UXDX conference, whose mission it is to help teams make the shift from projects to cross-functional product delivery. I’m always keen to learn more so please let me know your comments either below or you can find me on twitter @roryuxdx